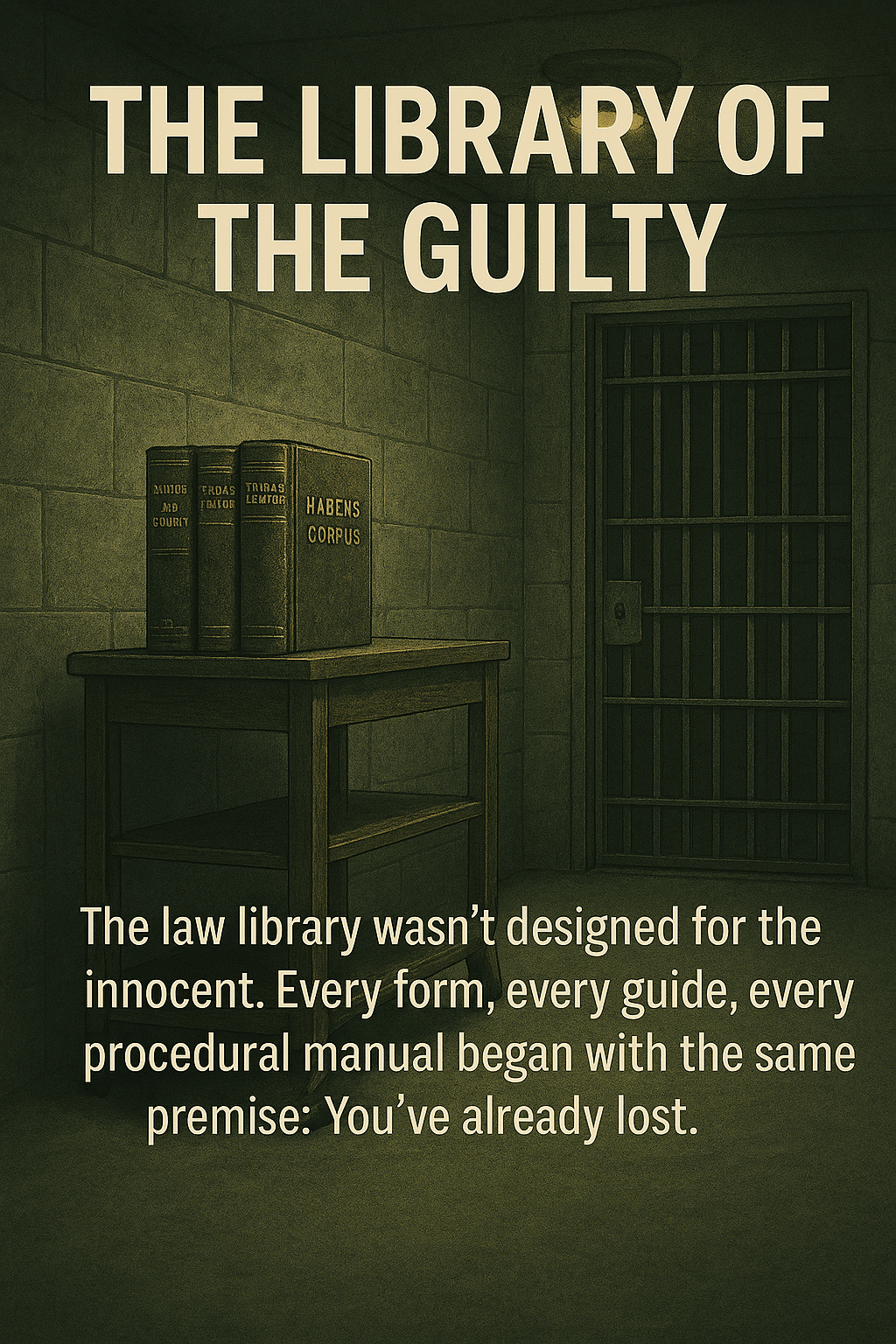

The Library of the Guilty

The law library wasn’t a room. It was a tablet. A digital portal locked behind privilege and classification. Only inmates housed in the pods had access. If you were on the southside—segregated, isolated, punished—you got nothing. No legal texts. No case law. No procedural guides. Just silence.

I was a pre-trial detainee. Legally innocent. Constitutionally protected. But Williamson County Jail didn’t care. Their system was built on the assumption of guilt. And their law library was designed for the already convicted—those filing appeals, not those fighting to prevent one.

The tablets were rationed. Timed. Monitored. And even when available, they were loaded with outdated materials focused on post-conviction relief. Habeas petitions. Sentence modifications. Nothing for someone trying to stop the machine before it crushed them.

I asked for access. I asked for federal codes. I asked for the tools to fight back. They gave me silence. Or worse—dismissive nods and vague promises. “We’ll see what we can do.” They never did.

On the southside, you weren’t just denied legal resources. You were denied identity. You were denied voice. You were denied the right to prepare your own defense. And when you asked why, they said it was a classification issue. A security concern. A staffing problem. But the truth was simpler: they didn’t want you to fight.

I’ve built systems. I’ve mapped institutional logic. I know how these places operate. And I know that denial of access isn’t a glitch—it’s a design. The law library was never about justice. It was about containment. It was about ritualizing guilt before conviction. It was about making sure that even the innocent felt condemned.

But I didn’t let it end there. I documented. I ritualized. I turned every missing page into testimony. Every denied tablet into curriculum. Every act of legal erasure into fire.

This chapter isn’t just about access. It’s about architecture. It’s about the silence that surrounds the innocent. And it’s about the refusal to disappear.

⚖️ Legal Foundation

- Bounds v. Smith (1977): The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that prison authorities must assist inmates in preparing and filing meaningful legal papers. This can be done by providing:

- An adequate law library, or

- Access to trained legal personnel.

- 28 CFR § 543.10–543.11: Federal regulations require wardens to establish law libraries and procedures for inmates to access legal reference materials, prepare documents, and consult legal counsel. Access must be “reasonable,” including during leisure hours when possible.

- Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ): In Texas, inmates are guaranteed “adequate, effective, and meaningful” access to courts. Depending on classification, inmates may receive:

- Direct access: Up to 10 hours per week in the law library.

- Indirect access: Legal materials delivered to housing units three times a week.

📚 What “Adequate” Means

An adequate law library must include:

- Up-to-date federal and state statutes

- Case law reporters

- Procedural rulebooks

- Self-help legal guides

- Basic supplies (paper, pens, photocopies)

Digital law libraries are increasingly common, but they must be comprehensive and inmates must be trained to use them effectively.